HEALTH & FITNESS

A monthly section on recreation and health, edited by Sue Dremann

Tooth or Consequences

High-tech dentistry makes toothless people smile

by Sue Dremann

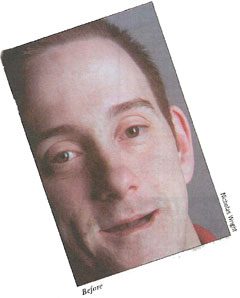

John Green didn’t have a tooth in his head late last month, but he was grinning.

He would soon be picking ribs from between his teeth — a set that would be all his own.

Just 27 years old, the Palo Alto resident has never tasted barbecued ribs, because he couldn’t tear meat from bones; and the only time he tried a steak, it stuck in his throat.

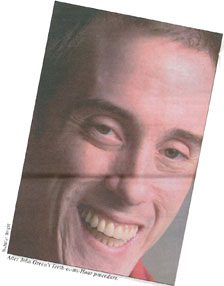

But on April 28, a revolutionary dental procedure gave Green a set of permanent pearly whites. Called Teeth-in-an-Hour, the new technique uses high technology to image and create models of a patient’s jaw, gums and natural bite, so prosthodontists can quickly and easily screw a set of pre-designed teeth into a patient’s jaw bones.

By dinnertime, most patients can sit down to a full course meal.

Prior to Green’s April 28 surgery, his teeth had been a mess, according to his dentist, Dr. Gary Laine, a Palo Alto prosthodontist who specializes in difficult cases. According to Green, his gums became inflamed starting when he was 10 years old. He couldn’t keep braces on because something was wrong with the enamel on his teeth. He couldn’t eat a regular sandwich, ripping and tearing at his food, instead biting.

By the time he came to Laine, his teeth were rotten from drinking soft drinks, and his gums were raw and inflamed.

“There were areas where it looked like a rat gnawed off” Laine said of Green’s back gums.

Green’s dental problems were partially genetic, and partially because he was a dental phobic, Laine said. Green was adopted, and didn’t know until recently that his birth mother and sister had the same jaw deformities he had, and a brother has the same kind of decaying teeth.

Few of Green’s teeth made contact, called malocclusion, which impaired eating and speaking. The widespread decay and malocclusion ensured that with time, Green’s remaining teeth would fall out.

Laine, who has practiced his specialized dentistry for 28 years, said Green’s was a “once in a lifetime case.” To correct his bite, Laine first extracted all of Green’s remaining teeth. Then, he coordinated with a plastic surgeon, who moved Green’s upper jaw 9 millimeters forward. (Moving the lower jaw would have obstructed Green’s airway.)

Laine created a special set of dentures. Thin slices of bone from the top of Green’s skull, which wear less than other bones, were added to bring the upper jaw forward. The dentures were then surgically attached.

In all, Green had six surgeries to add more surface area for his upper and lower jaw.

Laine then referred Green to Dr. Thomas Balshi, a Pennsylvania prosthodontist with Pi Dental Center, who had done more Teeth-In-An-Hour implants than anyone in the country, he said.

An imaging CAT scan created 3-D computer models of Green’s jaws, which were sent to Balshi and to Swedish dental implant maker Nobel Biocare, the inventor of Teeth-In-An-Hour. Technicians at Balshi’s company built a set of teeth based on plans developed from the computer images. They even matched the color of his gums.

Polished, they awaited Green’s arrival on April 28.

His patient sufficiently anesthetized, Balshi drilled the pre-marked holes for implants into Green’s jawbone, the consistency of which is between balsa wood and oak, he said.

Made of titanium, the implants, which look like tiny eyeglass frame screws, are bone-conductive, so that bone will grow to attach to them.

He screwed six implants into the holes in Green’s lower jaw. The custom set of teeth, made from resin, were then attached to the titanium framework. Then, Balshi drilled six implants into the upper jaw, repeating the process.

The entire surgery took one hour and 45 minutes.

When Green came out of anesthesia, he opened his eyes and looked in the mirror. Tears rolled down his cheeks. It was the first time he’d had teeth in six years.

Laine said he sometimes doesn’t think of the impact his work has on patients, but as he flew back from Philadelphia, he considered the changes he’s seen in John Green, as a young man he described as “a really nice kid.”

He’s watched Green turn his fear into interest, and his confidence and self-esteem grow. He will continue to evaluate Green’s upper teeth, which are made of a temporary resin material, for three months, fine-tuning the bite and aesthetics. Then, he’ll fabricate a final ceramic set of uppers and screw them in as individual crowns, which can be replaced if one wears down or becomes damaged.

Green’s teeth should last approximately five to seven years, Laine said, after which they should be replaced. New impressions will be made, and adjustments made, as Green’s jaw changes with age.

Green’s grin is wide.

“The sky is unlimited,” he said.

For years, he’s wanted to leave the Bay Area and explore different parts of the country. He’s already making plans.

He’s also adjusting to the feel of teeth, savoring the scents and flavors no longer blocked by dentures, and learning to speak clearly. He still forgets he has permanent teeth, and tries to take them out at night, as if they were dentures.

Eating, he’s finding, is revelatory. He ate a ham and cheese sandwich recently, and for the first time, he left teeth marks after each bite. There were clear, clean cuts, rather than sloppy tears, he said, grinning broadly.

Reproduced with permission from Palo Alto Weekly- May 10, 2006